INTRODUCTION

Berkshire Hathaway is a conservatively-run, well-capitalized business, managed by one of the greatest CEOs of all time. It uses minimal leverage, operates across many recession-resilient industries, and has grown earnings 20% per year since 1999. Businesses like this rarely trade for less than 20x earnings. Berkshire Hathaway trades for 7x.

While the company is best known for being a collection of “Warren Buffett’s stock picks”, it now derives a significant—and growing—portion of its value from another source: earnings from the company’s wholly-owned subsidiaries. We argue that this latter group—whose earnings exceed those of Amazon, Google, Netflix, Tesla, Twitter, and Uber; combined—is being under-appreciated by the market.

BUSINESS HISTORY

In 1964, Warren Buffett took control of a struggling New England textile manufacturer, named Berkshire Hathaway. Its net worth was $22m at the time. Fifty years and $411b later, Berkshire Hathaway is now the fourth largest company in the US, with a reach so wide it makes money nearly every time:

a plane is flown

a car is sold

a house is built

goods are transported to/from the West Coast

an iPhone is purchased

a lightbulb goes on in Nevada

someone drinks a Coke

a french fry is dipped in ketchup

So how did Buffett grow a modest textile company into a sprawling conglomerate—one that now owns dozens of operating companies and a stock portfolio worth $150b?

In the decades after taking control of Berkshire, Buffett steered the company through three major—and lucrative—shifts. He began in the late 1960s by acquiring insurance companies. Then he started using the insurance premiums generated by their operations to buy shares of publicly traded companies. Finally, in the 1990s, he began buying large businesses outright.

Phase I: Buying Insurance Companies to Generate Float

The first step took place in 1967, when Berkshire purchased a small Nebraskan insurance company called National Indemnity for $8.6m. Buffett was drawn to characteristics unique to the insurance business: cash—in the form of premiums—is collected years before claims are paid out. In the meantime, the insurance company is free to invest it. This money is commonly referred to as “float”. Buffett explains further:

“Float is money we hold but don't own. In an insurance operation, float arises because premiums are received before losses are paid, an interval that sometimes extends over many years. During that time, the insurer invests the money. This pleasant activity typically carries with it a downside: The premiums that an insurer takes in usually do not cover the losses and expenses it eventually must pay. That leaves it running an ‘underwriting loss’, which is the cost of float. An insurance business has value if its cost of float over time is less than the cost the company would otherwise incur to obtain funds.”

In other words: for most insurers, the combined cost of running their business and paying out claims usually exceeds the money they receive from premiums. Most insurers make up for these underwriting losses by profitably investing their float. If they just so happen to earn an underwriting profit—that is, if premiums ultimately exceed the cost of running the business plus the cost of claims—it’s simply a bonus.

Unlike most insurers, Berkshire consistently earns an underwriting profit. So not only does Berkshire get to invest the float, but it’s effectively paid to do so! Buffett says, “That’s like your taking out a loan and having the bank pay you interest.”

An insurer that consistently generates float and earns an underwriting profit is a great business. Still, Buffett saw more potential. Instead of investing the float in conservative and low-yielding bonds like a traditional insurance company does, Buffett took a new approach: he used the float to buy stock in other companies selling for reasonable prices.

Phase II: Using Float to Buy Partial Ownership of Other Companies (i.e., Stocks)

Throughout much of the 1970s and 1980s, Buffett used the proceeds from Berkshire’s insurance businesses to buy shares of a number of fantastic companies—such as Coca Cola, American Express, and The Washington Post—which were at the time selling for far less than their intrinsic values. By investing the borrowed money (i.e., float) that Berkshire was in effect being paid to hold, Buffett was able to lever his returns—earning Berkshire and its shareholders 20%+ per year. Even better, this leverage came from owned insurance operations rather than debt—which meant Berkshire reaped all the benefits of leverage without shouldering its traditional downside (such as interest expenses and an increase in risk).

Until the early 1990s, Berkshire Hathaway was in essence a lightly-leveraged, publicly-traded stock portfolio, managed by an unusually prudent investor. But as Berkshire grew in size, it became increasingly difficult to find opportunities in publicly traded companies that were large enough to move the needle. So Buffett changed track for the third time: he began acquiring operating businesses outright.

Phase III: Buying Full Ownership of Operating Businesses

Though Buffett did buy a few operating businesses in the 1970s and 1980s, it wasn't until the 1990s that he started doing so in earnest. Present-day Berkshire fully owns dozens of businesses, including: GEICO, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad, Dairy Queen, Benjamin Moore Paints, Clayton Homes, and ACME Brick. At first, the collective net worth of these businesses was dwarfed by Berkshire’s investment portfolio. And to this day it is the investment portfolio which remains the focus for most investors. But as Buffett continued to acquire simple, stable businesses that possessed what he deemed favorable long-term competitive advantages, their total value swelled. Today, they make up half of Berkshire’s intrinsic value.

PRESENT-DAY BUSINESS OVERVIEW

I. What is the Value of Berkshire’s Investment Portfolio (and Cash & Bonds)?

Included in this half of Berkshire’s value are its cash, bonds, and 5%-15% partial ownership stakes in companies such as American Express, Kraft Heinz, Apple, Coca Cola, IBM, Bank of America, and many others. Valuing Berkshire’s investment portfolio is simple. Since “cash is cash”, and the market prices the stocks and bonds every day, one needs only to look up the price and the number of shares owned by Berkshire to get an approximation of their worth:

An investor can then apply a premium or a discount, based on whether current market prices are under or overvalued. An argument could be made that Berkshire’s stock portfolio warrants a slight premium in light of Buffett’s investing prowess, but for simplicity’s sake we are assigning no premium, and assume the market is pricing each company correctly.

After summing up available cash, stocks, bonds, and preferred shares—and subtracting out deferred taxes Berkshire may eventually have to pay—we get $262b worth of investments.

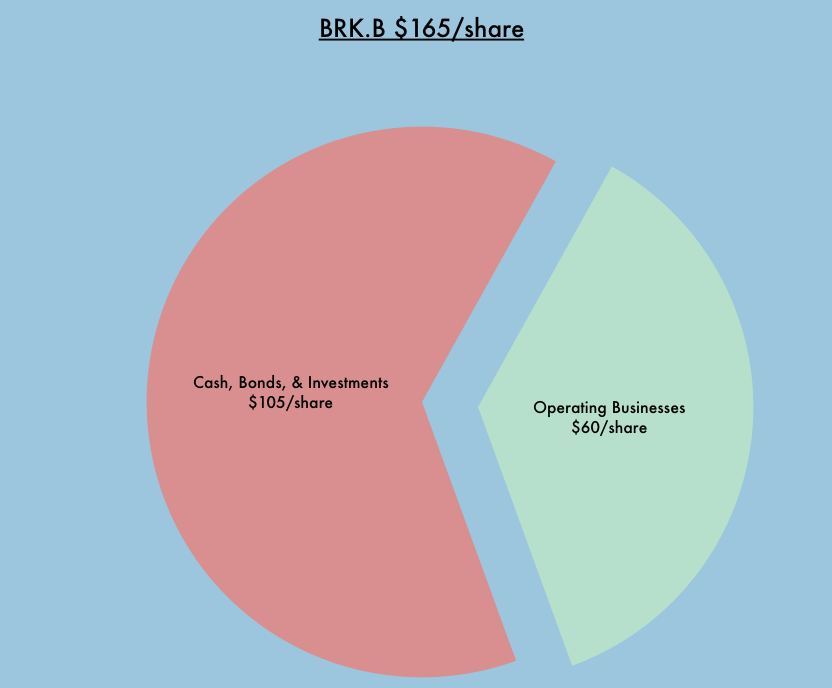

On a per share basis, this totals $105, or 64% of Berkshire's current $163/share price.

II. What is the Value of Berkshire’s Operating Businesses?

The rest of Berkshire’s value comes from its operating businesses. After backing out the $105/share of investments from Berkshire’s current share price ($163), the remainder—or $58/share—is what the market believes the operating businesses are worth.

Since the true value of its investment portfolio is more or less determined by the market, the question of whether or not Berkshire is properly valued at $163/share comes down to this: is $58/share a fair price to pay for Berkshire’s operating businesses? Considering these companies earned $8.56/share (pre-tax) in 2016, we feel that paying $58/share for this group—or 7x earnings—is a bargain.

Let’s break this down. Berkshire’s group of wholly-owned operating businesses has grown20%/yr for nearly two decades, earning $21b ($8.56/share) in 2016. Broadly speaking, its businesses fall into one of five segments: insurance; Berkshire Hathaway Energy (BHE); Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad (BNSF); Manufacturing, Services, & Retailing (MSR); and Finance & Financial Products.

1. Insurance

2016 earnings: $2.1b (10 % of total)

Companies: GEICO, General Re, National Indemnity, etc.

Since the purchase of National Indemnity in 1967, Berkshire’s insurance operations have become the largest and most profitable in the world. They have delivered 14 consecutive years of underwriting profits—a feat unheard of in the industry.

Aside from unusually consistent earnings, the insurance group provides Berkshire with an even greater benefit discussed earlier: float. At year end 2016, the company’s float—money that Berkshire holds but does not own—stood at over $100b. This free financing is available to Berkshire to acquire more businesses across a range of industries.

2. Finance and Financial Products

2016 earnings: $2.1b (10% of total)

Companies: Clayton Homes, XTRA, Marmon, CORT

This is Berkshire’s smallest group, made up of companies that specialize in mobile home manufacturing/financing, furniture rentals, and equipment leasing.

3. Berkshire Hathaway Energy (BHE)

2016 earnings: $2.7b (13% of total)

Companies: NV Energy, MidAmerican Energy, PacifiCorp, etc.

Berkshire Hathaway Energy is a group of regulated utilities, renewable power sources, and gas pipelines operating in Nevada, Utah, Iowa, Oregon, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Regulators allow these monopolies to exist, in exchange for a limit on how much they can earn. Even with these limits in place, this group of companies provides predictable and recession-proof earnings, with the important added benefit of allowing Berkshire to defer billions of dollars in taxes because of their large capital expenditure needs.

Said more simply: owning utilities is not a way to get rich; it’s a way to stay rich. And Berkshire intends on staying rich.

4. Burlington Northern Sante Fe Railroad (BNSF)

2016 earnings: $5.7b (27% of total)

Companies: Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad

Railroads play a vital role within the US economy; they ship goods from point A to point B more efficiently and cheaply than all other forms of transport. And because railroads require massive amounts of capital, land, equipment, and government cooperation, these companies are virtually impossible to duplicate—making disruption by a new competitor extremely unlikely.

The railroad industry is made up of regional duopolies, with BNSF and Union Pacific controlling the western US. While their earnings are cyclical and highly dependent on the health of the national economy, their long-term returns will almost assuredly be above average. Since acquiring BNSF in 2010 for $30b, the company has already earned a total of $24b, and is now the second largest contributor to Berkshire’s operating profit. Like the BHE group, BNSF requires large amounts of capital investment every year to maintain the infrastructure. And just like BHE, these capital outlays can be used to defer taxes at the parent-level for decades to come. Being able to “pay today’s taxes tomorrow” is another nice little form of float; one that lets Berkshire profitably—and tax-efficiently—reinvest billions of dollars back into both segments.

5. Manufacturing, Services, and Retailing

2016 earnings: $8.5b (40% of total)

Companies: See’s Candy, Lubrizol, Dairy Queen, Marmon, The Pampered Chef, etc.

This segment drives the lion’s share of Berkshire’s operating earnings. It is an eclectic collection of businesses, selling everything from Dilly Bars to partial ownership of private jets. As a whole, the group earns very respectable returns on capital—with almost no use of financial leverage. Furniture, ice cream, airplane parts, and underwear may not be the most trendy businesses in the world, but they’re safe, stable, and profitable, with many earning 15%-20%/year.

Together, these five groups earned $21b last year for Berkshire, or $8.56/share.

Are Berkshire’s Operating Businesses Being Fairly Valued by the Market?

Back to the question: Is $58/share a fair price to pay for Berkshire’s operating businesses?

For $58/share, investors are getting $8.56 of earnings generated by a group of stable companies that: earn solid returns on capital; have been vetted by an investor widely recognized as the greatest of all time; have grown earnings at 20%/yr since 1999; are unlikely to be disrupted by technological advances; and have long-term competitive advantages.

A standalone company with similar characteristics would probably trade above $170/share. Yet Berkshire’s operating business group trades for only $58. Perhaps if Berkshire renamed this part of their business Berkshire Hathaway AI Biotech Cloud Data Inc., it would it start trading at a more appropriate level. To put this in perspective, let’s imagine that certain popular tech companies started trading at a similar multiple to Berkshire’s operating businesses. Google’s share price would be $245 (versus actual $823); Netflix’s would be $4.50 (versus actual $142); and Amazon’s would be $64 (versus actual $884).

So how many times earnings should an investor be willing to pay for Berkshire’s operating businesses? Each of the five groups has different economic characteristics, so one could apply specific multiples to each (for example, 10x for insurance, 12x for BHE, 15x for BNSF, 15x for MSR, and 10x for Financial Products are probably appropriate). Doing so may yield a more precise (and probably higher) assessment of Berkshire's worth. But with either approach, the message is clear: the market is undervaluing Berkshire.

We apply a simple—and rather conservative—10x multiple to Berkshire’s group of operating businesses, which yields $85/share in value. When combined with its $105/share of stocks, bonds, and cash, this puts Berkshire’s intrinsic value at somewhere around $190/share—a 15% premium to today’s price.

Conclusion

50 years ago, Berkshire Hathaway was a struggling New England textile manufacturer. The business—which required a lot of capital, was barely profitable, and had no long-term competitive advantages—was not a good one. But Warren Buffett decided to buy it anyway, thinking the company’s assets (e.g., machines, factories, accounts receivable, etc.) were worth more than the price he could could pay for the entire business. After assuming control, business steadily deteriorated, and it became apparent the market had been right—Berkshire was a dud.

Half a century later, Berkshire Hathaway is far from a dud. In fact, it’s probably one of the best companies in the world. While the textile business is long gone, what remains is an investment portfolio worth $105/share, and a collection steadily growing, well managed, and very profitable businesses, that together earned $8.56/share in 2016. A company like that should trade for 20x earnings. Berkshire is available for 1/3rd that.