INTRODUCTION

Berkshire Hathaway is a conservatively-run, well-capitalized business, managed by one of the greatest CEOs of all time. It uses minimal leverage, operates across many recession-resilient industries, and has grown earnings 20% per year since 1999. Businesses like this rarely trade for less than 20x earnings. Berkshire Hathaway trades for 7x.

While the company is best known for being a collection of “Warren Buffett’s stock picks”, it now derives a significant—and growing—portion of its value from another source: earnings from the company’s wholly-owned subsidiaries. We argue that this latter group—whose earnings exceed those of Amazon, Google, Netflix, Tesla, Twitter, and Uber; combined—is being under-appreciated by the market.

BUSINESS HISTORY

In 1964, Warren Buffett took control of a struggling New England textile manufacturer, named Berkshire Hathaway. Its net worth was $22m at the time. Fifty years and $411b later, Berkshire Hathaway is now the fourth largest company in the US, with a reach so wide it makes money nearly every time:

a plane is flown

a car is sold

a house is built

goods are transported to/from the West Coast

an iPhone is purchased

a lightbulb goes on in Nevada

someone drinks a Coke

a french fry is dipped in ketchup

and the guy at DQ does this

So how did Buffett grow a modest textile company into a sprawling conglomerate—one that now owns dozens of operating companies and a stock portfolio worth $150b?

In the decades after taking control of Berkshire, Buffett steered the company through three major—and lucrative—shifts. He began in the late 1960s by acquiring insurance companies. Then he started using the insurance premiums generated by their operations to buy shares of publicly traded companies. Finally, in the 1990s, he began buying large businesses outright.

Phase I: Buying Insurance Companies to Generate Float

The first step took place in 1967, when Berkshire purchased a small Nebraskan insurance company called National Indemnity for $8.6m. Buffett was drawn to characteristics unique to the insurance business: cash—in the form of premiums—is collected years before claims are paid out. In the meantime, the insurance company is free to invest it. This money is commonly referred to as “float”. Buffett explains further:

“Float is money we hold but don't own. In an insurance operation, float arises because premiums are received before losses are paid, an interval that sometimes extends over many years. During that time, the insurer invests the money. This pleasant activity typically carries with it a downside: The premiums that an insurer takes in usually do not cover the losses and expenses it eventually must pay. That leaves it running an ‘underwriting loss’, which is the cost of float. An insurance business has value if its cost of float over time is less than the cost the company would otherwise incur to obtain funds.”

In other words: for most insurers, the combined cost of running their business and paying out claims usually exceeds the money they receive from premiums. Most insurers make up for these underwriting losses by profitably investing their float. If they just so happen to earn an underwriting profit—that is, if premiums ultimately exceed the cost of running the business plus the cost of claims—it’s simply a bonus.

Unlike most insurers, Berkshire consistently earns an underwriting profit. So not only does Berkshire get to invest the float, but it’s effectively paid to do so! Buffett says, “That’s like your taking out a loan and having the bank pay you interest.”

An insurer that consistently generates float and earns an underwriting profit is a great business. Still, Buffett saw more potential. Instead of investing the float in conservative and low-yielding bonds like a traditional insurance company does, Buffett took a new approach: he used the float to buy stock in other companies selling for reasonable prices.

Phase II: Using Float to Buy Partial Ownership of Other Companies (i.e., Stocks)

Throughout much of the 1970s and 1980s, Buffett used the proceeds from Berkshire’s insurance businesses to buy shares of a number of fantastic companies—such as Coca Cola, American Express, and The Washington Post—which were at the time selling for far less than their intrinsic values. By investing the borrowed money (i.e., float) that Berkshire was in effect being paid to hold, Buffett was able to lever his returns—earning Berkshire and its shareholders 20%+ per year. Even better, this leverage came from owned insurance operations rather than debt—which meant Berkshire reaped all the benefits of leverage without shouldering its traditional downside (such as interest expenses and an increase in risk).

Until the early 1990s, Berkshire Hathaway was in essence a lightly-leveraged, publicly-traded stock portfolio, managed by an unusually prudent investor. But as Berkshire grew in size, it became increasingly difficult to find opportunities in publicly traded companies that were large enough to move the needle. So Buffett changed track for the third time: he began acquiring operating businesses outright.

Phase III: Buying Full Ownership of Operating Businesses

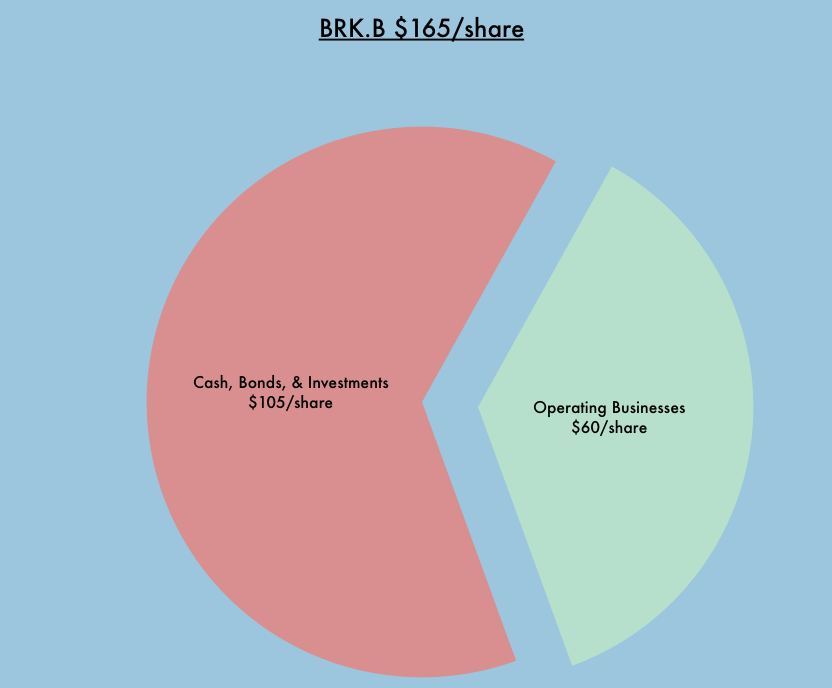

Though Buffett did buy a few operating businesses in the 1970s and 1980s, it wasn't until the 1990s that he started doing so in earnest. Present-day Berkshire fully owns dozens of businesses, including: GEICO, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad, Dairy Queen, Benjamin Moore Paints, Clayton Homes, and ACME Brick. At first, the collective net worth of these businesses was dwarfed by Berkshire’s investment portfolio. And to this day it is the investment portfolio which remains the focus for most investors. But as Buffett continued to acquire simple, stable businesses that possessed what he deemed favorable long-term competitive advantages, their total value swelled. Today, they make up half of Berkshire’s intrinsic value.

PRESENT-DAY BUSINESS OVERVIEW

I. What is the Value of Berkshire’s Investment Portfolio (and Cash & Bonds)?

Included in this half of Berkshire’s value are its cash, bonds, and 5%-15% partial ownership stakes in companies such as American Express, Kraft Heinz, Apple, Coca Cola, IBM, Bank of America, and many others. Valuing Berkshire’s investment portfolio is simple. Since “cash is cash”, and the market prices the stocks and bonds every day, one needs only to look up the price and the number of shares owned by Berkshire to get an approximation of their worth: